Four By Four #28

Four things to read, four things to see, four things to listen to, and four things about me

.

Four Things To Read

One Year, by Arielle Angel:

In the Guardian, Naomi Klein details the myriad ways that October 7th has been memorialized with the intent not to heal, but to retraumatize—or to spread the trauma to the diaspora like a virus, creating an identification with the Israeli victim that can be used as justification for limitless Israeli force. Klein speaks of memorialization, not mourning; she delineates the ways in which these diverge, with the former intentionally crowding out the latter. Indeed, for all the criticism directed toward the left broadly—and Jewish leftists, in particular—for not mourning 10/7 sufficiently, it seems clear that Jewish society writ large has, over the last year, demonstrated a failure to mourn. How else to explain the sacrifice of the hostages on the altar of vengeance? To account for the insistence on 10/7’s continuity with the Holocaust even as Jews hold opposite positions in regards to state power?”

Angel is the editor in chief of Jewish Currents, and I find this very pointed moment in her essay on the anniversary of Hamas’ October 7th attack both persuasive and moving, and to be sufficient reason to read the whole thing. One doesn’t have to agree with her, in whole or in part, to see that her position is one you have to take seriously.

§§§

Breaking In: The challenges of making it in the publishing industry from prison, by Lyle C. May:

”Less understood are the challenges and barriers imposed on incarcerated writers by the actual publishing industry, where editors, publishers, and agents rarely judge the merit of our work and instead fixate on false ideas about what our confinement may mean for the work we’re capable of producing. For us, success is much harder to come by than it should be.

I didn’t pay much attention to the issues surrounding incarcerated writers until I was asked by Pen America in 2019 if I’d be willing to make First Tuesdays part of its “Break Out” project, a joint endeavor with the Poetry Project “to (re)integrate incarcerated writers into literary community.” I agreed and in September 2019 and February 2020, First Tuesdays incorporated the work of two incarcerated poets, Edward Ji and Peter Dunne, into our monthly readings. Unfortunately, the pandemic shutdown happened the month after we included Dunne’s work and the potential for further collaboration fizzled out pretty quickly. May’s article, though, has reminded me of the importance of this issue—and that fact that I needed this reminder is an indication of how easy it is to forget these writers and what their voices bring to the table—which is why I encourage you to read it. If you care about writing, literary or otherwise, and the power of the printed word to change lives and contribute to the just transformation of the society in which we live, then the issue of how we treat incarcerated writers and their work needs to be part of your thinking.

§§§

What Translators Talk About When They Talk About Love, by Sonakshi Srivastava:

Love is an attempt at reconciling, accommodating, and acknowledging differences, an attempt at not giving up just yet. Forking away from indifference, love is an exercise in self-reflection. And what better way then, than prompting our translators to talk about their craft by pivoting the question on love? What if they were to talk about the challenges they face(d) while translating a particular noun, a particular verb, a particular idiom through the productive force of love?

This is an absolutely fascinating literary listicle of sorts, twenty eight translators giving short meditations on “the first word that they loved translating, how they arrived at that particular translation, and how they decided that it was the ‘right’ choice by working through the labyrinth of love and its valences.”

§§§

A Legal Justification for Genocide, Nicola Perugini and Neve Gordon:

Israel is not alone in using the human shielding allegation to justify violence against civilians; this strategy has previously been seen in conflicts ranging from the Vietnam War to the war against ISIS. However, the intensity and scope of how Israel has mobilized the human shields accusation in the past year is unprecedented. Parties alleging the use of human shields have typically restricted the charge to limited territorial areas; in contrast, Israel has cited Hamas’s underground tunnel system to cast every square inch of Gaza as a human shield.

Back in Four By Four #20, I included an article, also from Jewish Currents, called A closer look at the Gaza casualty data, by Marc Lynch and Sarah Parkinson. In that article, Lynch and Parkinson pointed out that Israel’s casualty estimates “posit[ed] all men in Gaza as Hamas combatants,” leading to a serious undercounting of the civilian casualties caused by Israel’s genocidal onslaught. It’s a rhetorical sleight of hand designed to undermine charges of genocide and humanize what Israel is doing as a necessary measure in combating the inhumanity of terrorists and their supporters. In the piece I linked to above, Perugini and Gordon address another facet of that strategy. “According to the laws of armed conflict,” they write, “the warring party that uses human shields, rather than the party that kills them, tends to be guilty of a war crime.” In other words, when it is true that one side in a war uses a hospital or an apartment building or a school that is occupied both by civilians and by legitimate military targets in order to force their enemy into killing of those civilians if it wants to attack those targets, the side that used those civilians as a shield is legally understood to be responsible for their deaths, not the side which actually killed them. By declaring what is essentially all of Gaza to be a human shield, Israel may not be trying to hide civilian casualties the way it does by declaring all men in Gaza to be combatants, but it is attempting to shift the blame and legal accountability for those civilian casualties it cannot deny onto Hamas. It makes me think of something Golda Meir said in 1969:

When peace comes, we will perhaps in time be able to forgive the Arabs for killing our sons, but it will be harder for us to forgive them for having forced us to kill their sons.

While these words were cynical when Meir said them, claiming for Israel a moral high ground I don’t think it ever actually held, I can, sadly, imagine Benjamin Netanyahu expressing a similar sentiment if and when Israel is ever able to declare victory over Hamas.

Four Things To See

Ethel Reed

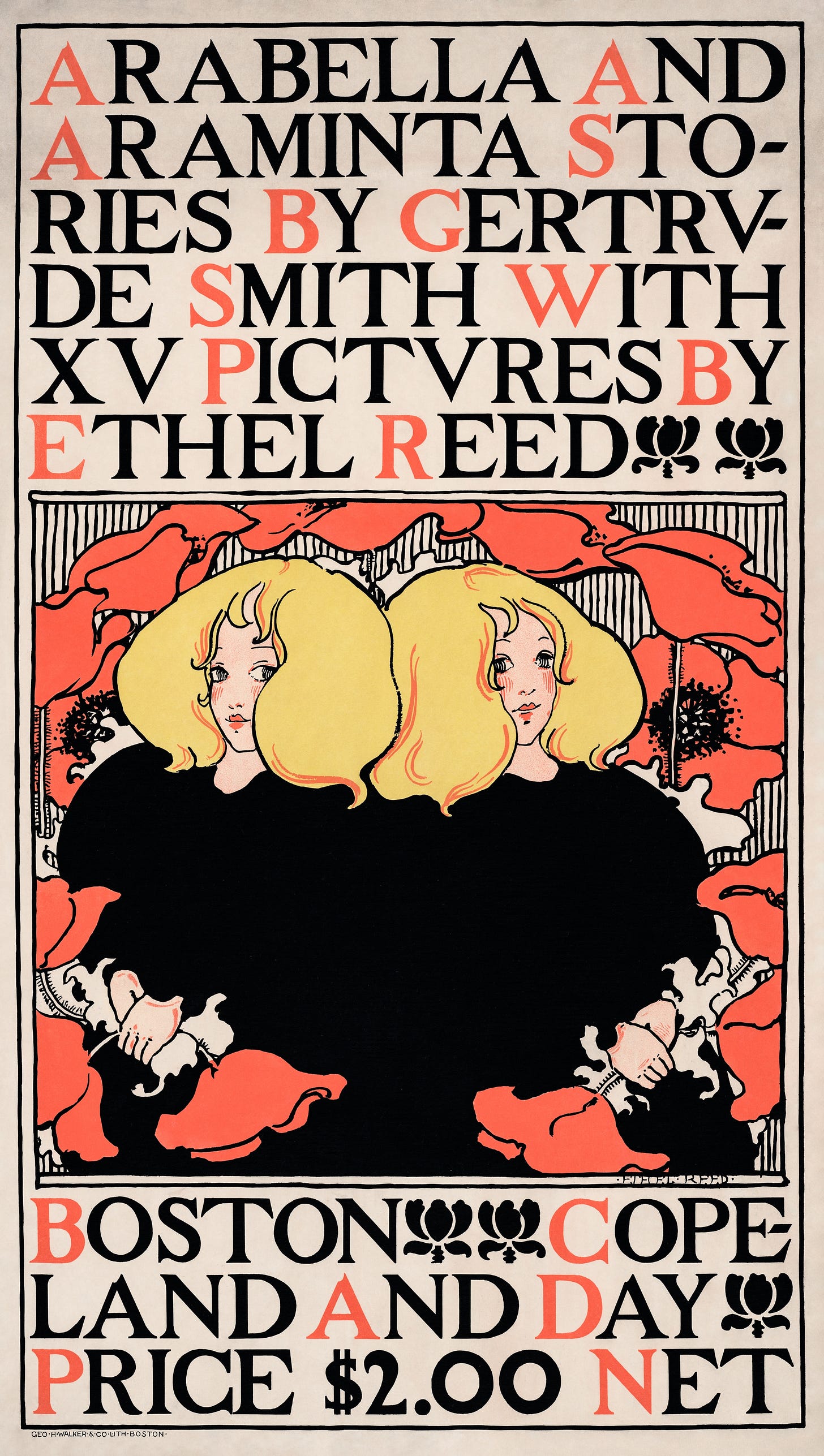

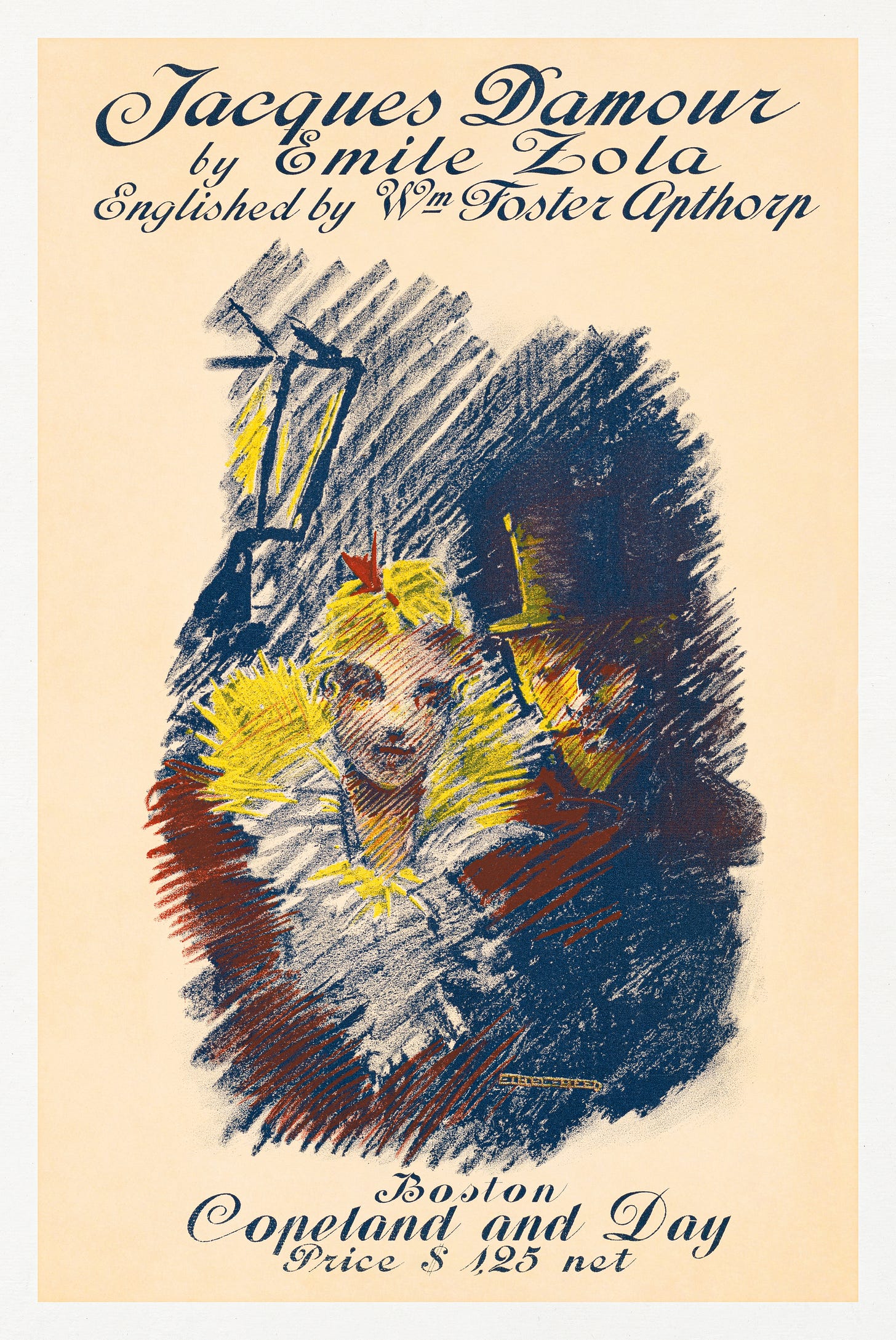

American graphic designer Ethel Reed (1874-1912) rose to fame at the early age of eighteen as an acclaimed poster designer. To everyone's perplex, she disappeared from historical records a few years later. Strongly influenced by the Art Nouveau movement and Japonisme, her artworks usually captured female figures and floral motifs along with the use of negative space and stark contrast between the figure and the background. She was also, as this article in ARTnews by Shanti Escalante-De Mattei demonstrates, a very interesting woman:

By the standards of her day, Ethel Reed was an impractical woman. Born in 1874, she wished to live independently, supporting herself with her art. Worse, she wanted to have sex with whom she wanted, when she wanted. Against all odds, she managed to live as she wished, becoming a nationally known illustrator with lovers to spare. But it was not to last, and Reed suffered an early, tragic death in 1912, before she even turned 40.

Here is a sample of some of her work:

Arabella and Araminta Stories (1895) - Art Nouveau poster of twin blonde girls

§§§

The Boston Sunday Herald (1895–1901) - vintage poster of a woman reading a newspaper

§§§

Jacques Damour (1896) poster of a man and a woman

§§§

The House of the Trees (ca.1895) vintage poster of a woman seated on lawn

Four Things To Listen To

Two Podcasts

Normally, I reserve this section for music, but I recently listened to two podcast that I thought worth sharing. For some reason, Substack is not allowing me to embed the podcast from Spotify or any other platform, so all I have for you are the links. I hope you will give them a listen. I think you’ll find them worthwhile:

Talking About Antisemitism: On The Nose is Jewish Current’s podcast. I wanted to share this episode with you because, while the left-wing publication is unapologetically critical of Israel, including the way charges of antisemitism are deployed to mute, discredit, or otherwise undermine that critique, this episode discusses the fact that antisemitism is nonetheless real, that it appears on both the left and the right—though in far greater quantity and virulence on the right—and that it is necessary to acknowledge and confront it as such, though perhaps differently depending on whether it comes from the left or the right. I found parts of the episode unsatisfying less because I disagree with what is said than because I thought the conversation about how to engage antisemitism when it comes from the left lacked both a level of specificity and a willingness at least to suggest that there is a line, or a point, beyond which that engagement becomes at best counterproductive and, at worst, self-destructive. Nonetheless, I think the episode is thought-provoking and well-worth listening to.

An Introduction to the Talmud: One of the motivations for the above episode of On The Nose was the fact that there have been social media posts and more arguing that the Talmud provides justification for what Israel is doing in Gaza. (I’ve tracked down some of them, though I’m not going to link to them because I don’t want to give them any traffic. They’re not hard to find if you want to Google them.) This got me to thinking about the difficulties I’ve had in the past trying to explain what the Talmud actually is and how it functions within Judaism to people who don’t know. This episode from the Literature and History podcast does a marvelous job of explaining just that. It’s long, and if you don’t want to listen, there’s a transcript on the episode web page, but it’s worth it.

§§§

Az Der Rebbe Zingt

This song was originally written to make fun of Chasidic Jews and what others saw as the slavish and unthinking way they followed their rebbes. Over time, though, it became an affectionate portrait of the fervor and sincerity with which they worshipped. I didn’t know this about the song until I read this article about Leonard Cohen’s version.

§§§

It Is A Legacy - Pierce Pettis

Four Things About Me

For most of my life, people have thought I was older than I was, mostly because I started losing my hair very young, at fifteen, so that, by the time I was an undergraduate in college, I was pretty much bald. I don’t know why, but this did not cause me the kind of anxiety hair loss stereotypically causes men. I remember, for example, a guy I worked with for a while when I was in my twenties—he was at least five years older than I was—who agonized over every strand of hair he found in his hair brush. He even told me once he would not drive on the highway with his window open because he was convinced the wind was making him lose his hair even more quickly than he already was, which, at least to my eyes, didn’t seem to be very quickly at all. Anyway, the fact that I looked older was often an advantage, since it meant that people treated me more respectfully, and even deferentially, than they would have if they’d known my true age. One time, though, when I was a college freshman, it decidedly did not. There was a party in my dorm and I was waiting on line to get a beer from the keg we’d set up in the kitchen. (The drinking age was eighteen back then.) A woman I recognized from orientation got online behind me. I was not surprised when she introduced herself as if she didn’t recognize me, since we’d been in different groups and hadn’t interacted. I introduced myself and we started making small talk. It became very clear very quickly, however, that she was interested in more than conversation. Eventually, she put her hand warmly on my arm and asked, “So, what subject do you teach here?” She thought I was a professor, which I found funny in an endearing sort of way, but she was mortified, rejected any attempt I made to turn the misunderstanding towards the possibility of our getting to know each other, and, after I reminded her that we’d met briefly at freshman orientation, she left the party. I never saw her again.

§§§

When I was a kid, I took magic lessons from a guy named Sam Winiger in the back of the convenience store he owned not far from where I lived. I’d ride my bike to his store on Saturdays around 4 PM, and he’d teach me sleight of hand. The first trick I remember learning was how to make a Superball change colors, which I’d watched him perform for his customers. He also taught me how to make toothpicks pass through each other, how to make a card I was holding disappear with a flick of my hand, and how to tie a knot in a piece of rope with one hand. In order to make the moves I needed to make to do those tricks look natural, I practiced them for hours in front of a mirror, complete with the accompanying patter, acting as my own audience. The point was to be able to make the moves without actually watching my hands, allowing me to do the tricks while looking at and talking to the audience, which is what made possible the misdirection that kept their attention away from the sleight-of-hand the trick required. This was my first experience in learning the discipline of a craft, a life lesson that has served me well as a poet. The one thing he said during our lessons that has stayed with me all these years is also a guiding principle I have carried with me. I thought I’d figured out how he did a vanishing trick he showed me. When I tried to expose the secret, and it turned out I was wrong, I was angry and disappointed in myself. “One of the most important things about being a magician,” he said, “is that you should never forget how to enjoy a good trick.” I learned later that Sam was a member of a group of magicians known as The Long Island Mystics.

§§§

I don’t know how old I was when George, the man who was my stepfather for a few years, took my brother and me to the Palisades Amusement Park, but one memory of that trip is permanently etched into my memory: trying to find my way through the Crazy Crystals Glass House, maze of mirrors. My brother found his way pretty quickly, but I kept banging my head into dead ends, so much so that I think I actually raised a small bump on my forehead. At one point, I thought I had succeeded because I walked back out into the park, but it turned out that I’d found my way back to the entrance. I didn’t want to go back in, but George told me I had to get through the right way, just like my brother, so I went back in and kept hitting my head, until the park attendant came in and led me out. I think I might have been crying. I was mortified, of course, especially because my little brother had outdone me, and George did not let me off the hook. He teased me about this for the rest of the day.

§§§

I took piano as an elective in my senior year of high school. I had never before taken piano lessons, though I’d been playing in my own, self-taught way for a couple of years. The woman who taught the class—I think her name was Mrs. Wilde—thought I had real potential and she encouraged me to play for the class’ recital a piece that I initially thought was way beyond my ability, Ernesto Lecuona’s Malagueña. I still have the sheet music. It was nothing like this professional performance, of course, but it was the first time I had ever worked my way through an entire piece of music by reading the notes and learning to play them. I remember how hard I worked to learn the piece and how happy and proud I was to be able to play it for an audience.

You are receiving this newsletter either because you have expressed interest in my work or because you have signed up for the First Tuesdays mailing list. If you do not wish to receive it, simply click the Unsubscribe button below.