Four By Four #19

Four things to read, four things to see, four things to listen to, and four things about me

Shameless Self Promotion!

An interview Catherine Fletcher did with me about T’shuvah was just published on Green Linden Press’ website. She asked really good questions that I thoroughly enjoyed answering. I do hope you’ll take a look. While you’re there, you should also check out the books Green Linden publishes. They’re doing really fine work.

Four Things To Read

A Flash of Darkness: Collected Stories of M. M. De Voe (Borda Books): This book of short stories by M. M. De Voe, the latest one I’ve finished in my reading of books by people I know, is a joy to read. The tales are funny, quirky, scary, and wonderfully twisted. They take me back to when I was a kid and loved to read science fiction and other so-called genre magazines, but they play with that form in such interesting ways that, for me anyway, they erase the hierarchical distinction that the term “genre” is usually employed to establish. The first story, for example, “Shutter,” is an unconventional revenge story involving a serial killer and the ghost of one of his victims, but it is also an easy-to-miss, very subtle, biting and in some ways devastating critique of patriarchal manhood and masculinity. That kind of political/social justice critique wends its way through most, if not all of these stories. This is a book well-worth reading—and, I would dare say, worth teaching as well.

Can Zionists Speak About The Nakba?, a transcript of Episode 74 of For Heaven’s Sake, a podcast of the Shalom Hartman Institute: Regardless of where you stand on the question of Israel and Palestine, I think this transcript is worth reading. (I have not yet had a chance to listen to the episode.) The people in this discussion are committed Zionists, by which I mean—as one of the participants, Donniel Hartman put it—people who are fully committed to “the right of the Jewish people to be a sovereign people” and to the existence of Israel as a sovereign Jewish state. They are, however, also people who are willing to ask the kinds of difficult questions that need to be asked on their side of the table if there is ever going to be peace. Here, for example, is a shortened version of the full quote from Donniel Hartman: “[C]an I as a lover of Israel…who embraces the right of the Jewish people to be a sovereign people…who experiences the victory of the Jewish people, can I look to my fellow citizens in Israel [he’s talking about Palestinian citizens of Israel] and…recognize that I’m walking in the midst of people [for whom] my coming home was not their independence day…for whom something has been broken?” The point he goes on to make is that, ultimately, no truly peaceful and productive resolution will be possible unless Jewish Israelis and their government—and by extension Jews worldwide and our governments—are willing to accept this fact. Neither he nor the other people on the podcast get into what that resolution might look like, which I think is wise since, especially given the Hamas attack on October 7th and Israel’s ongoing war in Gaza, there is precious little trust on any side of the table. Indeed, the question of trust is the subtext of the question that is the title of this episode, and it is articulated by Elana Stein Hain: [A]re we having this conversation [talking about the Nakba] to build trust? Are we having [this] conversation in order to think about our own morals? Are we having [this] conversation to do public statements [by which she means political posturing]?” I think the purpose of the discussion on this episode of For Heaven’s Sake is the second one. I do not think it is a sufficient conversation, nor do I agree with the underlying assumptions of most of the positions the various participants lay out, even if I find value in some of the positions themselves, but I was glad to know the conversation is taking place because I think it is a necessary one to have.

In Our Name: A Message from Jewish Students at Columbia University: There is much that is problematic in this open letter, not least the way its authors elide the move that conflates what I will call religious/cultural Zionism—by which I mean the explicit connection to the land of Israel/Palestine that is woven throughout Jewish texts and traditions, including the belief in the value of Jewish return to that land—with the political Zionism that resulted in the founding of Israel as a Jewish nation state. It is also easy to critique the letter—and I think this is a very valid critique—because, unlike the discussion I referred to above, it makes no mention of the Palestinians and their experience. Nonetheless, I think the letter is worth reading and some of its points worth grappling with, not because I think they are correct, but because they assert a right that progressives generally grant to every other marginalized group—the right to define their own experience on their own terms—and much of the anti-Zionist discourse that separates Zionism from Judaism/Jewish culture either implicitly or explicitly denies that right. Complicating this issue, of course, is the fact that, while Jews might be marginal not just in the United States and in most other countries throughout the world; while Israel, as a self-proclaimed Jewish nation, might be marginal among the nations of the world; the Jews in Israel most certainly are not marginal. Also, whether you choose to read the letter or not, this episode of the Jewish Currents podcast On The Nose uses a leftist critique of it as a jumping off point for a discussion that is well-worth listening to.

Dad Culture Has Nothing to Do With Parenting, by Saul Austerlitz: “Americans spend a fair amount of time describing things as “dad[,]” paint[ing] a picture of someone who is uncool, modestly embarrassing, and blissfully unconcerned with others’ judgments. But [that picture]…bear[s] little relationship to the actual work of raising children.” Austerlitz cites statistics showing that “Dads now spend more than triple the amount of time caring for children as they did in 1965” and the point of his essay is to ask why we continue culturally to hold on to “the old model of fatherhood” when it “bears less and less resemblance to [current] reality.” It’s a question worth pondering.

Four Things To See

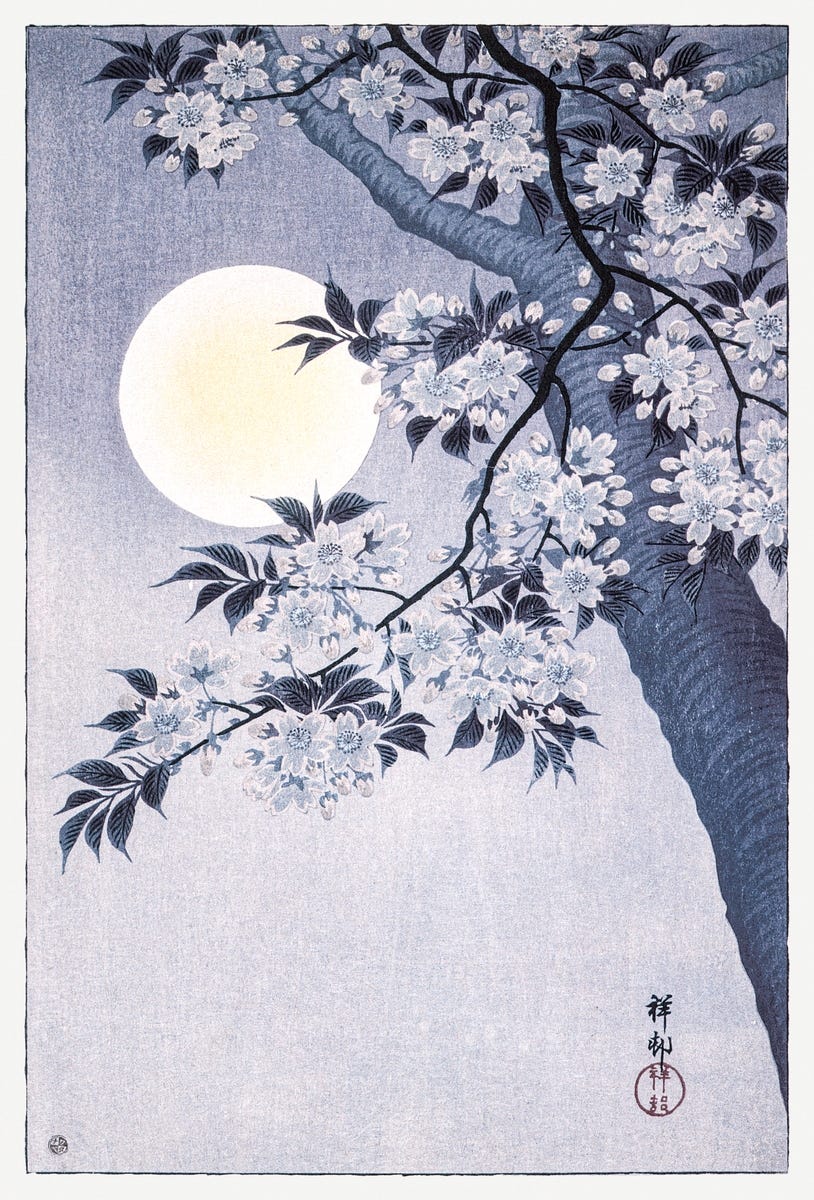

Two by Ohara Koson (1877–1945)

Ohara Koson (1877–1945), born in Kanazawa, northern Japan, was one of the foremost Japanese artists of the 20th century. He was renowned for designing beautiful illustration prints of birds and flowers (kacho-e) as part of the Shin-Hanga (new prints) movement. We have collected and curated Koson's best artworks for you to enjoy and download for free under the CC0 license.

Two peacocks on tree branch (1900 - 1930)

Blossoming Cherry on a Moonlit Night (ca. 1932)

Two by Marie Cassat

Mary Cassatt (1844–1926) was an American Impressionist painter, printmaker, and the embodiment of a “New Woman” of the 19th century. She spent much of her adult life in France alongside fellow contemporary Impressionists like Edgar Degas, Paul Cezanne, and Claude Monet. She was profoundly interested in depicting the woman’s perspective through art. She often drew pictures of ladies social lives, having tea in the garden during summertime.

Peasant Mother and Child (1895)

Spanish Dancer Wearing a Lace Mantilla (1873)

Four Things To Listen To

Ali Farka Touré & Toumani Diabaté - Ai Ga Bani

Mimi Fox : Live At The Palladium "Blues For Two"

Reza Vali The Book of Calligraphy No. 1: Hazin

Reza Vali The Book of Calligraphy No. 2: Zand

Four Things About Me

For a brief time in my twenties, I thought I might make a career for myself in Jewish community work, and so I took a job as what was then known as a Jewish Campus Professional for B’nai Brith Hillel/JACY. (I don’t know if this is still the title.) Back then BBHJ was the organization that provided leaders for the Hillel groups on college campuses. I was assigned to two campuses, one in downtown Manhattan and one in Nassau County on Long Island, neither of which had enough members to justify a full-time leader. I only held the job for about a year, but one situation I ended up being involved was actually a matter of life or death for an Iraqi Jewish student and his family back home. He was the child of an interfaith marriage, with a Muslim father and a Jewish mother. In Iraq, he’d been raised Muslim, but for reasons I don’t now remember, he’d secretly converted to his mother’s faith. The problem was that he needed to keep his conversion hidden from the other Iraqi students, who were all Muslim, for fear that they would report his conversion back home and that his family would be punished for his apostasy, a crime that carried the death penalty. I remember meeting the student, hearing his story, and I think I remember that his biggest concern was either finding a way to pray and/or in some small way to observe Shabbat and the holidays without getting caught. I recall a meeting with the college president to discuss the situation, and I think we eventually did find a solution. I wish I could remember more details, but this was almost forty years ago. Maybe one day I’ll dig out the journal I kept back then and see if I wrote anything more about this situation.

When I was a teenager, I played bass baritone bugle in the Knight of Columbus Drum & Bugle Corps. I originally wanted to be a drummer, but the corps’ director needed horn players, so that’s where he put me. I got to be pretty good, too, rising to the level of second seat, which meant I occasionally got to play solos. They didn’t have baritone horns in my high school marching band, though, so I tried unsuccessfully to learn trombone. I just could not get used to the difference between the valve-and-rotor system on the bugle–this was before they had two-valve bugles–and the slide on the trombone. The band director–I think his name was Mr. Fife (though I don’t know if I’ve spelled that correctly)–did get me a valve trombone, but for some reason I did not take to the instrument the way I did to the bugle. I left the drum corps once I started working summers as a camp counselor, and I have not tried since to learn any instrument other than the piano, on which I am mostly self-taught. (Sometimes I think I might like to take percussion lessons, though, or maybe voice lessons.)

I received my MA in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) from Stony Brook University in 1987. I taught English in South Korea–technically English as a Foreign Language (TEFL)–during the 1988–89 academic year. When I came back from Korea in September 1989, I was getting ready to apply for a job teaching English to South Korean immigrants for the New York State Department of Labor, when I received a call from Nassau Community College, asking me to come in for an emergency interview for a full-time teaching position. I had not actually applied for the job, but they knew me from my work in their Writing Center while I was getting my MA. In fact, they’d wanted to interview me when they were doing a formal search for new faculty that July, and had contacted my mother to get my number in Korea, but there had been no way I could get back to New York in time, and affirmative actions regulations prevented them from giving me a phone interview, while everyone else on their list interviewed face-to-face. The emergency interview came about because a member of the department had died suddenly and they needed to replace him. (I’m glad I did not know him.) I must have given a good interview, because they hired me. I have been teaching at Nassau Community College ever since.

I have never tried to write fiction.

You are receiving this newsletter either because you have expressed interest in my work or because you have signed up for the First Tuesdays mailing list. If you do not wish to receive it, simply click the Unsubscribe button below.