Four By Four #11

Four things to read, four things to see, four things to listen to, and four things about me

Four Things To Read

Donald Trump’s 2024 Campaign, in His Own Menacing Words, by Ian Prasad Philbrick and Lyna Bentahar: “‘If he says what he means and means what he says, and someday is able to implement it, it’s an existential crisis that the U.S. would face,’ said Barbara Perry, a presidential historian at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center.” When someone tells you who they are, you should believe them. This is a chilling read.

Sweeping Raids, Giant Camps and Mass Deportations: Inside Trump’s 2025 Immigration Plans, By Charlie Savage, Maggie Haberman and Jonathan Swan: “In a public reference to his plans, Mr. Trump told a crowd in Iowa in September: ‘Following the Eisenhower model, we will carry out the largest domestic deportation operation in American history.’ The reference was to a 1954 campaign to round up and expel Mexican immigrants that was named for an ethnic slur — ‘Operation Wetback.’” Again, he’s telling us who he is and we need to believe him.

Local Journalism Worth Reading From 2023: As you may know, one of the (perhaps unintended) consequences of so much of our lives going online has been a decrease in publications that cover local stories. I don’t usually share so many pieces from a single publication, but this piece from the Times actually links to local journalism from around the country. It’s well worth taking a look.

He Was Falsely Accused of Using AI. Here’s What He Wishes His Professor Did Instead, by Erik Ofgang: “Quarterman says his professor ran his essay response through an AI detection tool because she felt that his response was too general. When the essay was marked positive, she proceeded to accuse him of cheating, never considering that the AI detection tool could have logged a false positive, which can be fairly common.” The question of how to deal with one student whom you suspect of using an AI is, in some ways, quite simple. You treat it the way we used to treat possible instances of plagiarism before there were tools like Turnitin. Unless you already had absolute proof of some sort, you asked the student to explain their paper to you. If they could to your satisfaction, you were just expressing interest; if they couldn’t, you could usually get them to admit they’d plagiarized. One of the challenges with AI is that there’s such easy access, which makes it impractical to meet with every student whom you might suspect. This past semester, most of the papers I suspected ended up not fulfilling the assignment I’d given, so I could fail them without even having to go there.

Four Things To See: Images from the National Gallery

The University Singers of New Orleans, photographed in 1879 by Llewellyn A. Sawyer (1844 - 1923)

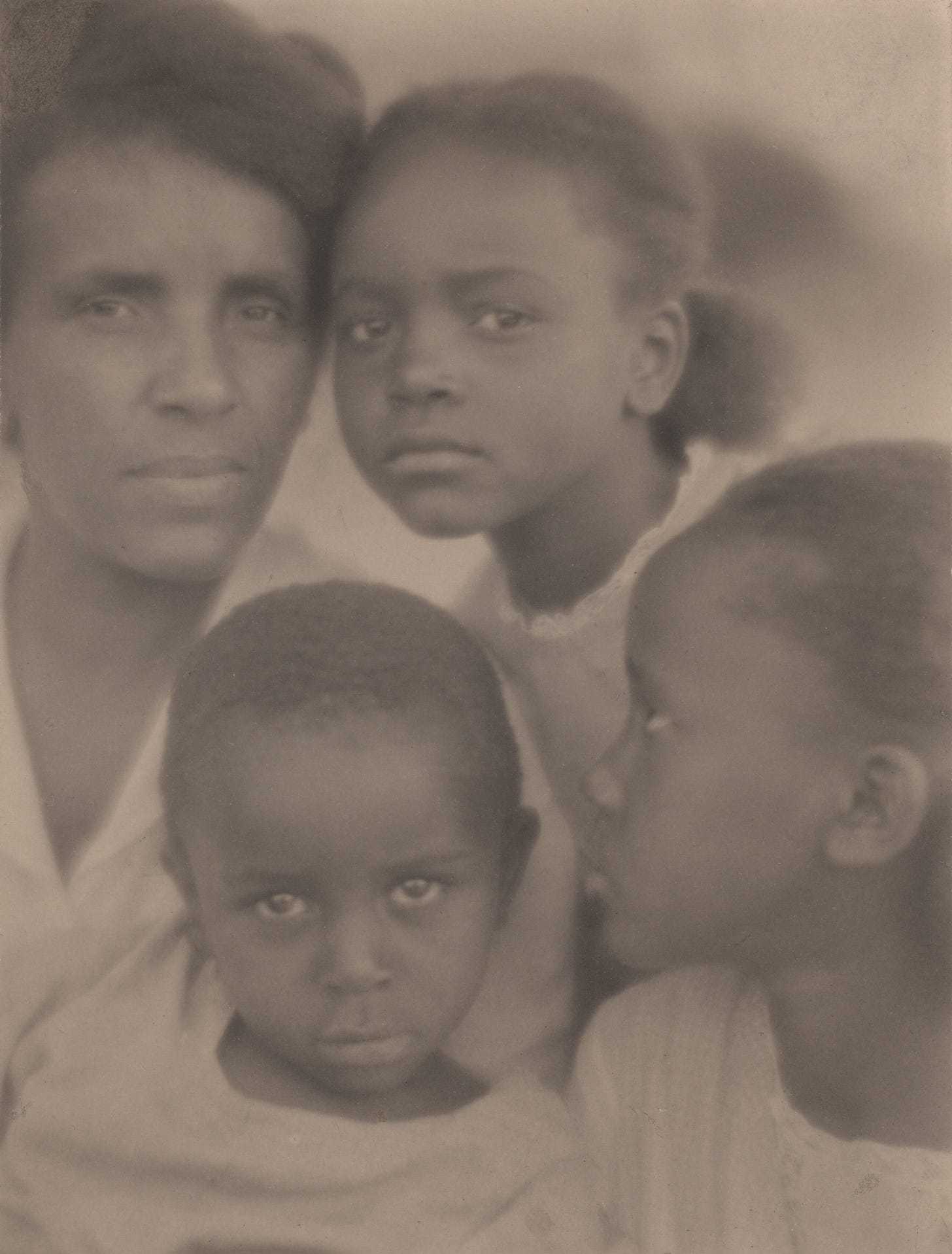

Portrait of a Family

Photographed by Edith R. Wilson (1864 - 1924) in 1922

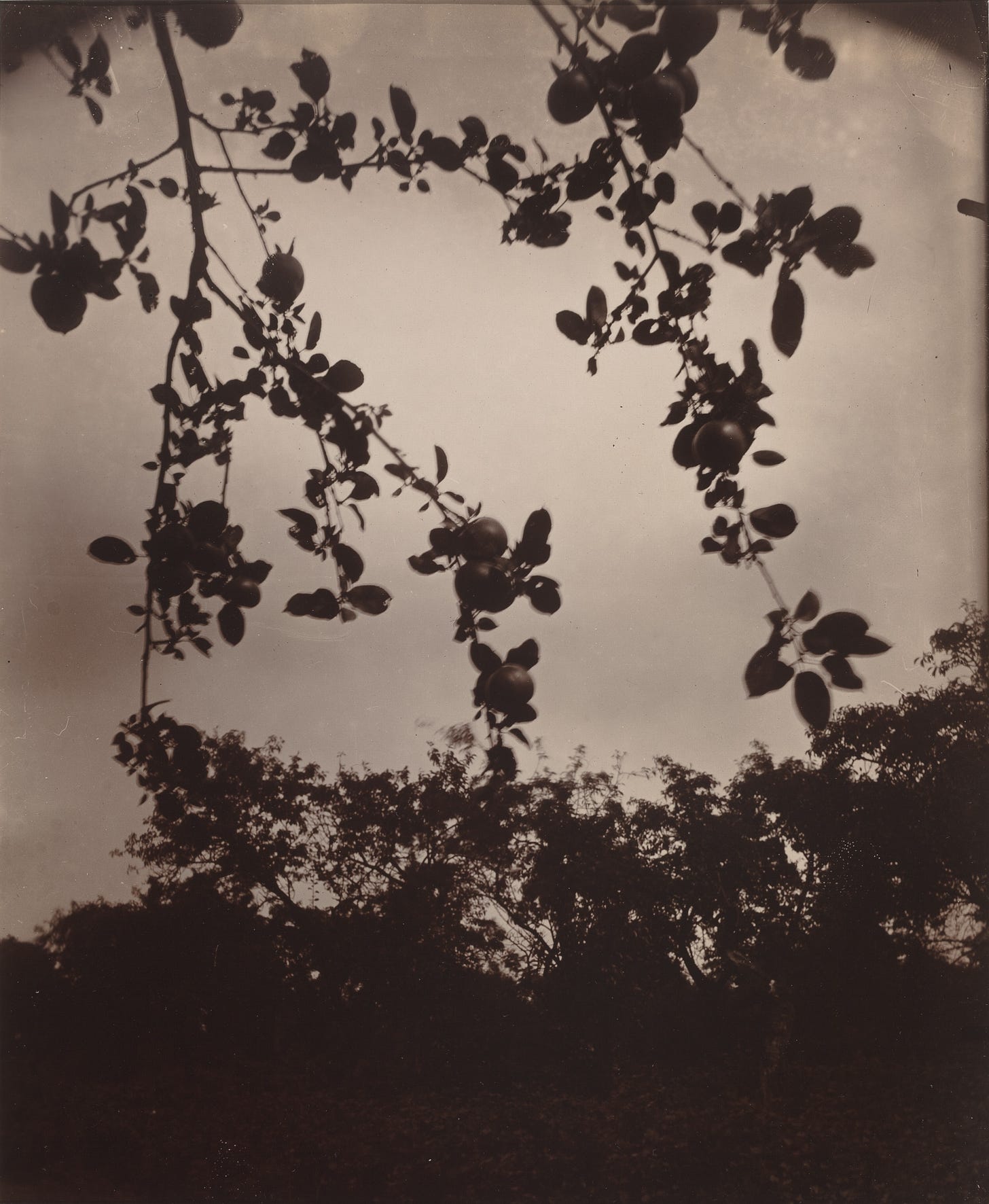

Branche de Pommier

Painted in 1922-23 by Eugène Atget (1857 - 1927)

Allegory on Copulation

By an anonymous Italian artist in the fourth quarter of the 15th century

Four Things To Listen To

Bad Bunny - Where She Goes

Big Mama Thornton - Rooster Blues/Ball & Chain - Hound Dog

Sarah Vaughan - Send In The Clowns

The Cab - Angel with a Shotgun

Four Things About Me

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the lessons I still carry with me from the yeshiva I attended from 8th through 11th grade, back when I thought I wanted to be a rabbi. I obviously changed my mind about that, and I know the rebbes who taught me would be very disappointed in how that change has shaped my life. Nonetheless, here are four lessons that I have carried with me for almost fifty years, and I am grateful for them.

When I was in eighth or ninth grade, some of my classmates circulated a petition asking the yeshiva’s administration for a change in policy that, if I recall correctly, would ease what they felt to be a conflict between schoolwork and certain aspects of their religious observance at home. I remember sitting in Rabbi Schubert’s Gemara class one morning when two of the girls who’d started the petition came in to ask if he would sign it. He told them no. He agreed with what they were asking for, he said, and would be happy to support them in discussions with the administration, but he would not sign the document itself because he did not want to lend his name to those students—and he knew there were some—who wanted the change to prioritize their own free time, not religious observance. Whether or not Rabbi Schubert was right about my classmates, I learned that morning that just because you nominally agree with someone, doesn’t mean you are in fact on the same side.

Rabbi Wehl, my tenth grade Gemara teacher, was the first person to give me (and my classmates, of course) permission to annotate a text I was reading. In fact, he told us that if we didn’t annotate the Talmudic text we were studying, then we weren’t really learning. How would we remember what our questions were, he asked, if we didn’t write them down? How could we deepen them and allow them to deepen us? Obviously, he wasn’t talking about all the questions one might have about a given text, just the ones that, as he put it, “could end up being with you your whole life.” That, he insisted, was why we had to learn to love those questions—he saw writing them down as an act of love—because “if you don’t learn to love them, the ones that really matter, how are you ever going to learn to love yourself?”

Tenth grade Gemara was also the class in which I got my first taste of a musar shmooze, a kind of (at least it appeared to me at the time, improvised) moral exhortation. Sometimes Rabbi Wehl would take up almost the whole class period passionately urging us to be better Jews. I tended to experience these talks more as exercises in shaming than the truth-telling tough love I think Rabbi Wehl intended them as. No matter what he was talking about, though, at some point he would pause, look around the room and say, “I am only speaking to one of you right now. I don’t know which one of you it is, and tomorrow it may be someone different, but whoever you are, you’re the one who needs to hear this. You’re the one I am meant to teach today.” That conviction echoes through my own pedagogy, not in the moral and ethical sense Rabbi Wehl was concerned with, but in the sense that I know I am at my best as a teacher when I don’t try to control which of my students is learning what.

My teacher in eleventh grade Gemara was Rabbi Wahrman. What I remember most about him, though, is something he said to me when I came back to visit the yeshiva during my first year of college. The school had structured its classes so that we were able to graduate in 11th grade. I could have gone the following year to a yeshiva in Israel before enrolling in college or I could have entered a program in which I would continue my religious studies in the morning and take college classes in the afternoon, getting a head start on all my friends who were in public school. I turned both those opportunities down, however, and instead went back to public school for 12th grade. Rabbi Wahrman was the only former teacher who did not try to guilt-trip me over that decision. Instead, he asked if I was involved with the Jewish community at the college I was attending, and when I told him that I was working as an advisor to a USY youth group, his face lit up. “So you’re still connected!” he said. “That’s the most important thing.” That moment was my first lesson in the fact that one could choose orthodoxy for oneself without being dogmatic about it when it came to others.

Photo of #4 by Jason Blackeye on Unsplash.